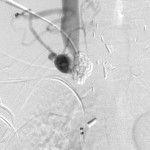

- Central venogram through the RIJV: There is chronic total occlusion of the distal RIJV.

- Central venogram through the right external jugular vein (REJV): There is chronic total occlusion of the distal REJV.

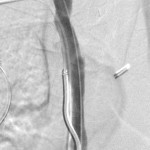

- Terminal central venogram through the REJV: A guidewire has been passed through the recanalized vein into the IVC.

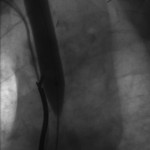

- Mid-phase balloon inflation of the RBCV and SVC: Incomplete dilation of the central veins.

- Late-phase balloon inflation: Complete dilation of the central veins.

- Central venogram via the REJV after track dilation: Complete restoration of luminal patency.

- Fluoroscope of the chest after intervention: A double-lumen catheter is tunneled into the right atrium.

Clinical problem: A 43-year-old male patient with end-stage renal disease was referred to the interventional radiology service for a new dialysis access and relief of signs of superior vena cava syndrome. He had had many failed autogenous and non-autogenous arteriovenous accesses, and recently reverted to tunneled dialysis catheters as he waited for new arteriovenous access. Most recently, he suffered cardiac arrest at another facility while receiving a tunneled dialysis catheter.

Angiographic findings: There is chronic total occlusion of the distal right internal jugular vein (RIJV), right external jugular vein (REJV), right brachocephalic vein (RBCV), and the superior vena cava from previous catheterizations. The occlusions prevent the insertion of a new catheter by conventional means. Other findings from other imaging modalities revealed occlusions of the common femoral and iliac veins as well as the SVC.

Endovascular interventions: The distal right internal jugular vein was identified with a high-frequency ultrasound probe and accessed with a micropuncture set. Venogram through the access revealed complete occlusion of the distal end of the vein as well as collaterals at the root of the right neck. It was not possible to pass a guidewire through the access into the right atrium, so a second access was gained into the right external jugular vein under ultrasound guidance. Central venogram through this access showed it was also completely occluded, but it was possible to probe through it into the right atrium with a stiff guidewire and a catheter. With the stiff guidewire advanced through this access into the inferior vena cava, a balloon was used to dilate the occluded venous track. After confirming that the lumen of the vessel was restored, a double-lumen, cuffed catheter was advanced into the right atrium and retrogradely tunneled through the upper right chest and out the skin. The final chest radiograph shows the well-curved catheter in the right atrium.

Practical points:

- It is possible to recanalize chronic venous occlusions, even when such prospect seems bleak.

- Such occlusions result from previous central venous catheterizations or manipulations. The presence of cardiac electrodes through the right subclavian vein in this patient did not help matters.

- Such occlusions when bilateral and total can cause superior vena cava syndrome, whose symptoms may be pronounced by fluid retention when the occlusions preclude dialysis and there no other means for dialysis.

- Recanalizing such occlusions can be life-saving when there are no other ways to dialyze a patient.