What Are Hemodialysis Accesses?

The kidneys eliminate excess water and impurities from the body. When they fail the body retains the impurities and water making the patient sick. The best treatment for renal failure is renal transplant, but for several reasons this is not always practicable. 2 substitutes, hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis are available to keep patients alive.

In peritoneal dialysis the membrane lining the patient’s abdominal cavity exchanges the impurities and excess water with a liquid called a dialysate injected into the cavity through a catheter inserted into it.

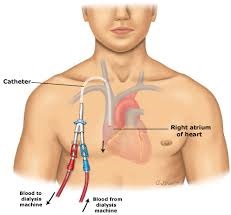

Dialysis catheter

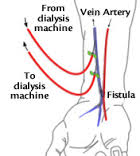

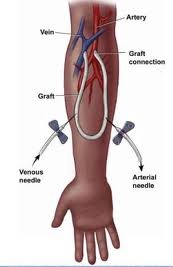

In hemodialysis, blood drawn from the patient is passed through a machine that removes the impurities and excess water and returned to the patient’s blood stream. A catheter with 2 channels is inserted into a large vein in the patient by an interventional radiologist and blood is drawn through one channel to the dialyzing machine and returned to the patient from the machine through the second channel. In another method of hemodialysis, surgeons connect an artery to a vein either directly in arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) or by interposing an artificial tube between them in arteriovenous grafts (AVGs).

AV Fistula

AV Graft

Blood is drawn from and returned to the patient through these channels after passing through a dialyzing machine. Catheters, AVFs, and AVGs are all hemodialysis accesses, but AVFs and AVGs are more desirable than dialysis catheters.

Do Hemodialysis Accesses Fail?

Yes, they fail or malfunction, but there several things interventional radiologists do to restore their function. The dialysis catheter may leak, break, obstruct, or become infected. Usually, every effort is made to preserve the access unless doing so imperils a patient. When that is the case, the catheter may be exchanged for a new one using the same venous access, or a new venous access created if using the old access is unwise or not practicable.

AVFs and AVGs may fail to ‘mature’ after their creation and be unusable. Interventional radiologists can assist their maturation with creative interventions. But their commonest problem when mature is their unpredictable, sudden cessation to function. This is often due to a narrowing in their venous limb that develops over time, slowly diminishing the flow of blood through the access until it suddenly ceases. The blood in the graft and any length of vein before the obstruction congeals, completing the problem. Interventional radiologists have ways of reopening the venous narrowing, removing the blood clot and restoring function to the access. Sometimes these accesses fail because they develop large bulges called aneurysms from being punctured repeatedly. These can also be treated with stents to prolong the life of the access. To avoid these surprises, the accesses are often monitored periodically with ultrasound or angiography.