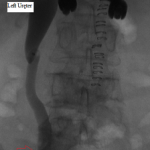

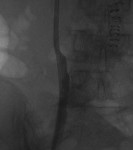

The above images belong to a middle-aged woman with cervical cancer, who developed impaired renal function when the cancer invaded and obstructed her distal ureters. Efforts by urologists to stent her ureters from below through her urethra failed, because the ureteral orifices were invisible. She was referred to the interventional radiology service for ante-grade intervention through the kidneys. Because she was prone on the table for the procedure, there is seeming reversal of her right and left sides.

Access was gained from the back into a dilated posterior calyx of each kidney and secured with a sheath. Antegrade pyelogram on each side revealed marked ureteral and calyceal dilation due to complete obstruction of the distal ureter. A wire was advanced into the urinary bladder past the obstruction, which was dilated with a non-compliant balloon when it resisted the deployment of a nephroureteral stent. The stent was successfully deployed after the balloon dilation.

The ureters can be obstructed by benign and malignant disease in or outside them. When this happens, the flow of urine is disturbed, slowly progressing from delayed emptying of the ureters to complete cessation of flow into the urinary bladder.

Pressure rises in the collecting system above the obstruction as urine accumulates above it. If the obstruction is not relieved or the upper urinary tract not decompressed, the increased pressure impairs renal function and ultimately stops urine production. The resulting retention of water and the impaired elimination of waste products of metabolism sicken the patient and may prove lethal. In addition, the stagnant urine may become infected, leading to sepsis that may overwhelm the patient. For these reasons such obstructions must be relieved or the accumulated urine drained.

Ureteral obstructions are best managed by urologists, but when they prove high-grade and urologically non-crossable, an interventional radiologist can approach them by passing instruments from the back, through the kidneys, past the obstructions, into the urinary bladder using imaging guidance while the patient is sedated.

If obstructions are easy to cross, internal ureteral stents may be placed across them, with one end of the stent in the renal pelvis and the other in the urinary bladder. The stents should be changed periodically through the urethra by urologists or interventional radiologists. Sometimes, as in the patient whose images are displayed above, the obstruction must be predilated to permit insertion of the ureteral stents. Alternatively, a drainage catheter called a nephrostomy catheter can be deployed into the renal pelvis to drain urine into a bag attached to it without crossing the obstruction.

Internal ureteral stents are preferable over nephroureteral stents, which are also placed by interventional radiologists but differ from ureteral stents in having their proximal segments outside the patient, so that urine not only drains down their internal segment into the urinary bladder, but is also diverted into a bag attached to the hub of their external proximal end. They differ from nephrostomy catheters in having an internal component continuous with their external component and that runs down the ureter to the urinary bladder.

Nephrostomy catheters and nephroureteral stents are indicated in patients with total urinary incontinence, because with them not all the urine made by the patient flows into the urinary bladder; some is diverted externally. In total urinary incontinence, which can be caused by multiple disorders, the patient is constantly wet with urine escaping past an incompetent bladder neck or across an abnormal connection between the urinary tract and the vagina. Nephroureteral stents and nephrostomy catheters are also easier to exchange by interventional radiologists, but come with the nuisance that the patient has to manage their external component.