History

A mother brought her 2-year-old son to the hospital because she had noticed that his left buttock was larger than his right buttock. There was no antecedent trauma and the mass was painless. According to his mother, the child had been well until the mass appeared, but except for its unsightliness, it did not border the child. He was attended by a pediatric surgeon who noted an otherwise healthy child and ordered cross-sectional imaging that revealed a fatty solid lesion centered in the boy’s left ischiorectal fossa and perineum but infiltrated the deep pelvis and the left gluteal muscles. He watched the child closely over 2 years and partially debulked it because of continued growth. The child did well but the mass continued to grow requiring near-complete excision when he turned 4. Except for gait imbalance and some fecal and urinary incontinence the child did well and is still being seen at the pediatric surgery clinic.

Radiologic Findings

![BM9656_MR_axialT1[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/BM9656_MR_axialT11-300x187.jpg)

![BM9656_T2FS_axial[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/BM9656_T2FS_axial1-300x240.jpg)

![BM9656_T1_coronal[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/BM9656_T1_coronal1-274x300.jpg)

![BM9656_T2_sagital[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/BM9656_T2_sagital1-209x300.jpg)

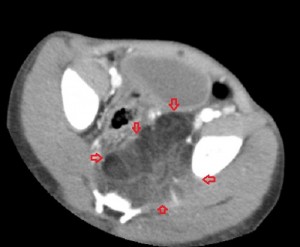

The 1st image in the top panel is a plain radiograph of the child’s pelvis depicting enlargement of the left hemipelvis and shift of the pelvic structures to the right due to a poorly-revealed mass with patches of fat in it. The 2nd and 3rd images in the top panel are CT images of the pelvis and they show a multilobulated mass centered in the left ischiorectal fossa and perineum infiltrating the lower retroperitoneum, medially, and the left gluteal muscles, laterally. Its medial extent is well-defined and similar in attenuation to subcutaneous fat, while its lateral extent is less defined and of soft-tissue attenuation. The mass compresses the rectum while displacing it to the right and pushes the urinary bladder upwards. There is no bony invasion or destruction.

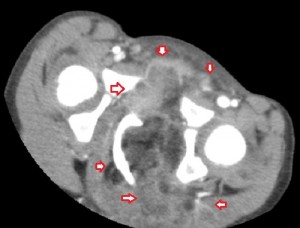

All the images in the lower panel are MR images (from left to right, axial unenhanced T1; fat-suppressed T1 post-gadolinium; coronal T1 without fat suppression; fat-suppressed sagittal T2). They show the extent of the disease better than CT and confirm that it is primarily lipomatous with little soft-tissue content. It infiltrates most of the left gluteal muscles, occupies the entire left perineum and ischiorectal fossa, and extends proximally in the retroperitoneum to the level of the sacral promontory.

Radiologic Diagnosis: Liposarcoma

Pathologic Findings

![BM9656_Gross[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/BM9656_Gross1-290x300.jpg)

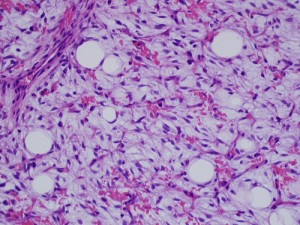

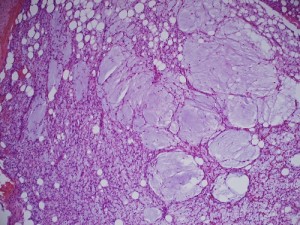

Gross image (far left image) shows a multinodular reddish and pinkish fatty mass, while the low-power and high-power microscopic images (middle and far right images) reveal a mucoid matrix with lipoblasts at different maturational stages (spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells to univacuolated cells with compressed nuclei).

Pathologic diagnosis: Lipoblastomatosis.

Discussion

Current World Health Organization Committe for the Classification of Soft Tissue Tumors organizes benign lipomatous disorders of soft-tissues into 9 classes of disease: lipomas, lipomatosis, lipomatosis of nerves, lipoblastoma and lipoblastomatosis, angiolipoma, myolipoma, chondroid lipoma, spindle-cell lipoma, and hibernoma. These tumors are unified by the presence of fat in them though mixed with varying amounts of other mesenchymal derivatives (blood vessels, muscle, cartilage, fibrous tissue, etc.). Lipoma, at 50%, is the commonest of them.

Benign lipomatous tumors of soft tissues vary in prevalence, presentation, and management and rely for their prepathologic diagnosis on the ability of an imaging modality to show their fat content. They can also affect bones, joints, and tendon sheaths, but a discussion of all benign lipomatous tumors of musculoskeletal tissues is beyond the scope of this writing. We will dwell on lipoblastoma and lipoblastomatosis.

Lipoblastoma is a rare benign tumor of embryonal white fat that occurs in infants and young children. It is believed to consist of embryonal lipoblasts growing in a myxoid matrix, most cases (nearly 90%) occurring in children below 3 years; it is uncommon in those aged 10 years and above. Lipoblastoma is a fast-growing tumor, typically painless and may show propensity to regress and involute with time. It occurs 3 times more frequently in males than in females.

A distinction is made between lipoblastoma and lipoblastomatosis, the former a circumscribed lesion confined to the superficial tissues, and the latter an infiltrative disease of the superficial tissues and their underlying musculature, like our patient. Lipoblastoma represents 70% of this form of lipomatous soft tissue tumor, while lipoblastomatosis represents 30%. As stated, the natural history of these tumors is to regress and there are reports of lipoblastomas regressing over a 5-year period and lipoblastomatosis over 1 year, but occasionally, as in our patient, growth is so rapid as to necessitate early debulking surgery. Neither has a malignant potential.

These tumors cause symptoms by the effects they have on local tissues. For example, lipoblastomas, which tend to occur in upper extremities, neck region, chest wall, mediastinum, and the retroperitoneum may cause fever, intermittent airway obstructions, vomiting, anorexia, and abdominal pain. On occasion their only observable effect is swelling or disfigurement of the affected area or region, as in our case.

On gross pathology, lipoblastomas may be red, pink, white, tan, light yellow or yellowish-grey and frequently measure less than 5 cm and are well-encapsulated, while lipoblastomatosis, being infiltrative, tends to be larger and less defined, a point illustrated by this patient. At histology, they show univacuolated or multivacuolated lipoblasts, myxoid stroma, spindled-to- stellate mesenchymal cells, a plexiform capillary network, and mature lipocytes. Ultrastructurally, they consist of cells ranging from perilipoblasts (spindle cells) to mature adipocytes.

The imaging appearance of lipoblastomas and lipoblastomatosis depends on the amounts of fat and myxoid tissue they contain and these tend to vary with age. Tumors richer in fat are lucent on radiography, very echogenic on sonography, low-attenuating on CT, and isointense to subcutaneous fat on all pulse sequences on MRI (as demonstrated by the present case). They do not enhance as much as those rich in myxoid stroma, which are less radiolucent on radiography, iso-attenuating to soft-tissue on CT and, like most soft-tissue tumors, are low- to iso-intense on T1 and hyperintense on T2 on MR imaging. When lipoblastomas contain more myxoid elements they are indistinguishable from liposarcoma, a malignancy, even at histology. However, liposarcoma is so rare in early childhood that when a tumor with histologic features that suggest it is seen in a child less than 2 years old, it is invariably a lipoblastoma, not liposarcoma. Lipoblastomatosis shares similar imaging characteristics to lipoblastoma except that it is more infiltrative and so may be more destructive.

The treatment of both lipoblastomas and lipoblastomatosis is wide surgical resection when they cause symptoms or manifest rapid growth since their natural tendency is to regress. Sometimes a tumor may require several debulkings to achieve remission because there is a 9% to 25% recurrence rate, particularly with lipoblastomatosis because it is infiltrative. In our case, the pediatric surgeon hoped to leverage the tumor’s regressive tendency but intervened because of rapid growth.

Acknowledgement

The gross photograph and microscopic images were provided by Kimiko Suzue, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, Chicago, Illinois.