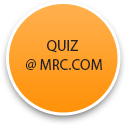

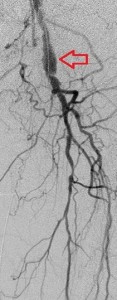

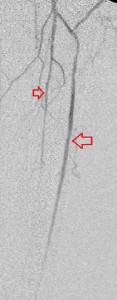

Top panel: Pre-intervention run-off angiogram of the left lower extremity showing, from left to right, irregular left common femoral artery (LCFA) arrowed on the 1st image, absent left superfical femoral artery (LSFA) or any bypass conduit on the 2nd image, sketchy descending collaterals from the left deep femoral (LDFA) that reconstitute a faint shadow of the left popliteal artery, arrowed on the 3rd image. The last 2 images faintly show three-vessel run-off below the left knee. The anterior tibial artery is most opacified, followed by the posterior tibial artery; the peroneal artery peeps through the upper edge of the last image. Note how weakly visible these vessels are due to the poor inflow from above.

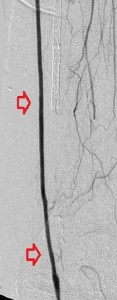

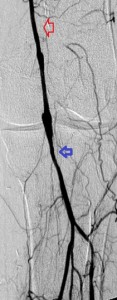

Bottom panel: Post intervention run-off arteriogram of the left lower extremity showing, from left to right, the proximal and distal segments of the re-opened left femoro-popliteal bypass (red arrows on images 1, 2, and 3). Contrast the full-column opacification of the below-knee left popliteal artery, arrowed blue on the 3rd image, and the enhanced visibility of the three-vessel subpopliteal domain to their vestigial appearances on the pre-intervention images, when they were poorly fed through collaterals.

Arterial bypasses are surgical contructs that connect normal proximal and distal segments of an arterial tree to deliver more blood distally by avoiding a diseased segment of the tree. The preferred bypass conduit is a patient’s native vein, but when such is unavailable or what is available is unacceptable or insufficient, a synthetic conduit is used. Bypasses may be long or short depending on the length of the arterial obstruction. Their longevity varies and depends on the nature of the underlying arterial disease, the flow of blood into and out of them, the technical challenge in creating them, the skill of the operating surgeon, a patient’s blood pressure, and the nature of the bypass conduit.

Bypasses fail if blood flow through them is restricted by upstream arterial disease or short-circuited through large proximal side trunks; by a poor distal run-off, a diseased pedal arch or a weak, impoverished, or discontinuos link between the two; by hypotension, especially soon after their creation, because this induces slow flow through them and hastens clot formation; synthetic conduits tend to stay open shorter than native veins. Finally, technically-challenging creations or those constructed by inexperienced hands tend to fail quicker than their counterparts.

Early bypass failure, within 30 days, precipitates acute ischemic symptoms and demands urgent surgical intervention. It frequenctly is due to unattended disease in the inflow or outflow channels, a mechanical error in its creation, hypotension, or problem with the conduit. Later failure causes less dramatic symptoms that demand less speedy intervention and, when it happens within 1 to 2 years of a bypass’ creation is often due to the development of anastomotic intimal hyperplasia. Intimal hyperplasia is physiologic smooth muscle enlargement in the wall of a native vein when it is subjected to high-pressure arterial flow and can be treated with balloon angioplasty. Bypass failure after 2 years is frequently due to progression of the underlying atherosclerosis, either in the inflow or the outflow vessels. There are times, however, when no identifiable cause for a failure exists and this is more prevalent with synthetic conduits.

When blood flow into or out of a bypass fails, it thromboses and its salvage includes gaining access into it and removing the clot in addition to determining the reason for its failure. Such clot removal may be mechanical, as is frequently the case in acute graft failure, or through thrombolysis, as is the case in later failures. The above images illustrate the later scenario in which the patient presented about 1 year after a left femoropopliteal bypass was fashioned for them. I crossed into the lumen of the bypass conduit from a right common femoral arterial puncture and advanced an infusion cather into it for overnight continuous alteplace infusion following a bolus dose. (I favor 5 to 10 mg of alteplace bolus, followed by continuos infusion at 0.5 mg per hour, in company with fixed unfractionated heparin infusion at 500 units to 600 units per hour after a bolus dose of 3000 units to 5000 units). In this case the bypass proved to be a vein conduit connecting the left common femoral artery, proximally, to the mid popliteal artery, distally, without intimal hyperplasia. The cause of the failure was diminished inflow due to left iliac disease.The final runoff images reveal a three-vessel tibial domain continuous with a near-normal plantar arch.