History

This is a 57-year old woman taken to a community hospital for care following a motor vehicle collision.

Radiologic findings

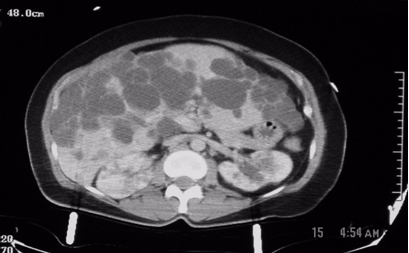

Figure1: These are two contiguous computerized axial tomographic sections of the abdomen obtained after intravenous infusion of contrast.They show an enlarged liver that contains multiple cysts ranging in size from a few to several centimeters, diffusely spread throughout the organ. The kidneys also contain several (>5 total, bilaterally) similar though much smaller cysts but they are not very large. The pancreas, at least to the naked eye, is spared. There are no other obvious abnormalities; the lady, fortunately, had no significant intra-abdominal injuries from her trauma.

Radiologic diagnosis: Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Disease (ADPD).

Radiologic differential diagnosis

Polycystic Liver disease.

Tuberous sclerosis.

Autosomal recessive polycystic disease (ARPD).

Von Hippel Lindau disease.

Multiple simple cysts in the liver and kidneys.

Discussion

The definitive diagnosis of this case hinges upon the patient’s family history, genetic evaluation and, if necessary, tissue procurement. Based on the radiographic appearance of her liver and kidneys, however, the two prime suspects should be ADPD and Polycystic liver disease. Of the two, the former is more likely because of commonality and the absence of hepatic fibrosis.

Hepatic cysts may be congenital or acquired. The acquired variety is due to trauma, inflammation, parasitic infection or tumor. The cysts are usually not as numerous as in this case. The congenital variants are rare and autosomal dominant; 50% of them may have polycystic kidney disease (1).

Tuberous sclerosis and von Hippel Lindau (vHL) disease belong to the phakomatoses, a group of neurocutaneous disorders that may have cysts in the viscera. The former may show bilateral asymmetric renal polycystic lesions but differs from ADPD by the presence of renal angiomyolipomas and involvement of the lungs, skin and brain. vHL disease on the other hand comprises cerebellar hemangioblastoma, retinal hemangiomas and, occasionally, pheochromocytomas. This patient had none of these.

It is uncommon to have this degree of hepatomegaly and bilateral multiple renal cysts due to the presence of multiple simple cysts in the liver or the kidneys. The term ‘polycystic kidney disease’ encompasses both the autosomal dominant (ADPD) and the autosomal recessive (ARPD) forms of polycystic kidney disease. Although there is considerable effort to distinguish the two forms of the disease, for obvious genetic reasons, there are cases in the young in which the imaging features of the two forms of the disease are present in the same child, making it impossible to confidently allocate the disorder to a particular category. There have been reports of cases previously ascribed to one form of the disease by prenatal US that over time evolved to the other variant. Therefore, in children with polycystic kidneys imaging cannot hope to provide a conclusive diagnosis, but can complement clinical findings. In adults, the features of ADPD, a confirmed family history of the disease, and its imaging features make its diagnosis relatively easy.

In ARPD, there is always involvement of the liver by fibrosis with or without ectasia of the bile ducts similar to that seen in Caroli’s disease (6). The patient, always the index case in a family, typically presents younger but may appear in adolescence with hematemesis due to portal hypertension; the disease, though, is not compatible with longevity and is not a likely diagnosis in this case.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (Adult polycystic kidney disease, Potter type III disease) is the fourth commonest cause of end-stage renal disease (5). Its inheritance is by autosomal transmission and the disease has 100% generational penetrance but a variable expressivity. At least there are descriptions of three genetic variants of the disease (4); 85% of cases (PKD1) are due to an abnormality at chromosome 16q13.3, while 15% (PKD2) are due to an abnormality at chromosome 4q21-23. The third genetic locus, yet unmapped, is a rare cause of the disease. In the disease, there is heightened predisposition to the formation of epithelium-lined cysts in renal tubules and Bowman’s capsules that grow to variable sizes surrounded by fibrotic tissue and that ultimately destroy the kidneys (4). There may be cysts in the liver (25-50%), pancreas (9%), kidneys, spleen, thyroid, ovaries, uterus, testis, seminal vesicles, epididymis and the urinary bladder. Other associated abnormalities include saccular (berry) aneurysms of the circle of Willis (10 to 16% of autopsy cases and as many as 41% of patients undergoing cerebral angiography), aortic root abnormalities, mitral valve prolapse, hypertension, azotemia, proteinuria, lumbar and abdominal pain and abdominal and inguinal hernias. Renal failure is usually a late manifestation.

Ultrasound is a useful screening tool for ADPD in adolescents and contrast-enhanced CT or MRI are recommended when the US results are equivocal or if there is need to exclude complications of the disease (e.g. renal cell carcinoma) or other differential diagnosis (e.g. Tuberorus sclerosis) (7,8,9). The complications of the disease include hematuria (due to a ruptured cyst), renal calculi (composed of urate or calcium oxalate), renal cell carcinoma (difficult to diagnose but not commoner in the ADPD population than in the general population) and chronic renal failure (which develops in 50% of patients) (3). The prognosis of the disease depends upon the development of renal insufficiency. When the serum creatinine level is consistently above 1.5mg/dL, the disease has entered a progressive phase of renal insufficiency. Risk factors that accelerate the progress of renal failure include: male gender, multiple pregnancies, the PKD1 genotype, hematuria, hypertension and proteinuria (3). Treatment is by hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis or renal transplantation. ADPD patients on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis fair as well or better than patients with end-stage renal disease from other renal pathologies.

References

1. Zheng D, Wolfe M, Cowley BD Jr, Wallace DP, Yamaguchi T, Grantham JJ. Urinary excretion of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003 Oct;14(10):2588-95.

2. Bisceglia M, Galliani CA, Senger C, Stallone C, Sessa A. Renal cystic diseases: a review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006 Jan;13(1):26-56. Review.

3. Grantham JJ. Mechanisms of progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 1997 Dec;63:S93-7. Review.

4. Grantham JJ.The etiology, pathogenesis, and treatment of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: recent advances.Am J Kidney Dis. 1996 Dec;28(6):788-803. Review.

5. Fall PJ, Prisant LM.Polycystic kidney disease. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2005 Oct;7(10):617-9, 625.

6. Sgro M, Rossetti S, Barozzino T, Toi A, Langer J, Harris PC, Harvey E, Chitayat D. Caroli’s disease: prenatal diagnosis, postnatal outcome and genetic analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Jan;23(1):73-6.

7. Dimitrakov DY, Dimitrakov JD, Despotov TB. Ten-year clinical and ultrasonographic follow-up of siblings from families with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2002;44(4):10-2.

8. Lackner E, Jobges M, Schirmer F, Hummelsheim H. Intracranial aneurysms and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease] Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2002 Aug;70(8):438-42. German.

9. O’Neill WC, Robbin ML, Bae KT, Grantham JJ, Chapman AB, Guay-Woodford LM, Torres VE, King BF, Wetzel LH, Thompson PA, Miller JP. Sonographic assessment of the severity and progression of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the Consortium of Renal Imaging Studies in Polycystic Kidney Disease (CRISP). Am J Kidney Dis. 2005 Dec;46(6):1058-64

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges the tireless work of Obidike Nwakudu, MD in the publication of this article. Dr. Nwakudu was a resident in the Division of Family Medicine at Mount Sinai hospital, Chicago when he did the work.