Normal drainage of bile may be impaired by cancer, benign strictures, or gallstones that obstruct the biliary pathways and cause bile to accumulate above the obstruction. This dilates the ducts above the obstruction and forces bile to “leak” into the blood stream, turning the eyes, skin, and urine yellow – biliary jaundice. Biliary malignancy can occur in any segment of the bile ducts – within and without the liver – and frequently portends poor prognosis. Similarly, nonmalignant obstruction of the biliary tree can affect any segment of the tree, but it is not necessarily fatal.

Relieving malignant obstruction is important and can provide a patient quality time before death, if such is inevitable. This can be done surgically (by resecting the tumor and constructing a direct connection between the small bowel and the biliary tree, called choledochojejunal anastomosis), endoscopically (by deploying a stent across the malignant obstruction during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopacreatography (ERCP)), or percutaneously (by gaining access into the biliary tree through the skin and deploying a drainage catheter or a stent across the obstruction). The choice of the method of intervention depends on the patient’s preference, the skills available in an institution, and the location of the tumor; in general terms, non-resectable tumors should be approached endoscopically and stented or percutaneously if endoscopic intervention fails or is not feasible. The following cases of mine illustrate percutaneous biliary interventions.

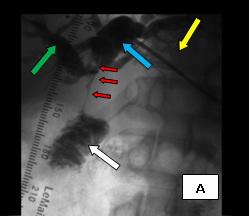

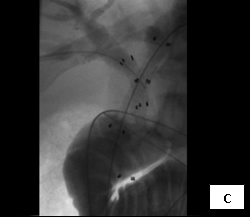

The first case (images A, B, and C), was an elderly man who came to me from a nursing home with advanced carcinoma of his common bile duct that severely narrowed the duct. The string of contrast outlining the very narrow common bile duct (red arrows, image A) and the dilated ducts above the narrowing (green and blue arrows, image A) testify to the severity of the disease. His left hepatic duct (blue arrow, image A) had been percutaneously decompressed elsewhere with a drainage catheter (yellow arrow, image A), but he remained jaundiced and ill.

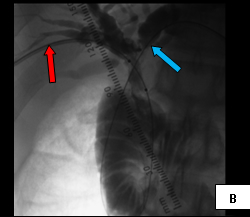

So, coming through a fresh percutaneous access on his right side (red arrow, image B) and through the drainage catheter already in his left hepatic duct (blue arrow, image B), I concurrently deployed stents across the obstructed confluence of the hepatic ducts and across the common bile duct. The effect of the treatment is evident by comparing images A and C: decompression of the dilated right and left hepatic ducts, relief of the critical obstruction of the common bile duct, and quick movement of copious amounts of the injected dye (which correlated with the movement of bile) into the duodenum.

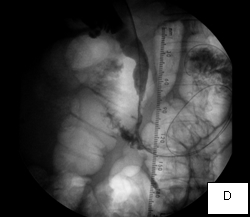

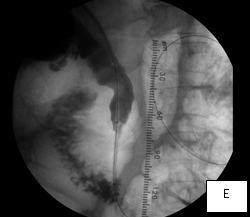

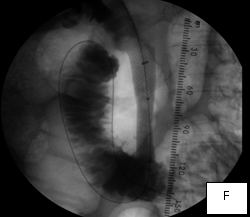

The second case was a woman with obstructive jaundice from cancer of the head of the pancreas, which produced a tapering narrowing of her common bile duct. In her, I crossed the diseased duct by cannulating a right intrahepatic duct from a right percutaneous puncture. Once I secured the access with a sheath, I was able to cross the obstruction with a stiff glidewire (image D) over which I deployed a Wallstent (image F).

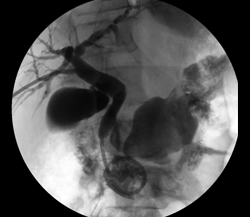

The third case illustrates percutaneous biliary drainage, which is the insertion of a drainage catheter from the skin, through the liver, into the duodenum, crossing the site of biliary obstruction. It is often the first step towards percutaneous biliary stenting and serves to decompress dilated biliary ducts and allow their inflamed walls to simmer down while waiting for the pathologic diagnosis of the obstructive disease before deploying a metallic stent across it. (Such staged approach is unnecessary if a non-metallic stent is employed in treating the disease, because such stents are easily retrievable should the final diagnosis recommend alternative forms of treatment; metallic stents, once deployed, are not removable.) Secondly, percutaneously stenting a biliary obstruction at the time of initial crossing is sometimes prolonged and challenging and risks seeding the blood stream with bacteria from the inflamed and friable biliary wall, causing sepsis.

In this woman, crossing her obstructed ampulla of Vater at ERCP failed, so I had to percutaneously deploy a biliary drainage catheter across it while waiting for the result of her biliary brushings. The single image illustrates the deployed catheter across the obstruction.